THE PERSONAS: how pop-psychology butchered Jung's persona, and how we need to "radicalize" Jung and combine him with Lacan

I. INTRODUCTION

II. JUNG’S PERSONA

The persona is a

concept introduced by psychoanalyst Carl Jung to refer to the “mask” we are

playing in a certain social context. It is, fundamentally, a role we play,

so it has inherent connections to the concept of “acting” and “play-pretend”.

When a literal theatre actor is playing their character, we can say that they

are putting on a new “mask”, they are playing a character, and that new

character is the new persona. In my real-life I am Ștefan

Boros, a writer, student and musician, but if I decide to drop all of this for

an acting career, I can jump on stage and play, for example, Hamlet, and thus I

will embody a new persona: on stage I pretend to be Hamlet (son of the

late king and nephew of the present king, Claudius) while being Ștefan again after I get off stage.

Just like actors pretend

to be someone who they are not when they are on stage, just like that Jung

noticed that all people have various personas that they switch in depending on

the context in which they are in. At home we behave in one way, at work we act

completely different, in a certain group of friends our personality might

completely change and so on; and it seems that we are in a constant

never-ending process of pretending to be someone who we are not. To quote Jung

himself, from the beginning of his 1957 interview:

“I noticed with my patients… these people that

are in public life, they have a certain way of presenting themselves.

For instance, the doctor: he has a certain way, for instance, he has good

bedside manners, and he behaves as one expects a doctor to behave! He may even

identify himself with it and believe that he is what he appears to be! He must appear

in a certain form, unless people don’t believe that he’s a doctor. (…) So the

persona is partially the result of the demands society has. And, on the other

side, it is a compromise with what one likes to be, or as one likes to appear.

So, take for instance, a person who also has his particular manner of acting

that corresponds to the general public expectation, and he also behaves in a

certain way such as his own fiction about himself is portrayed to the public.

Thus, the persona is a certain complicated system of behavior which is

partially dictated by society and partially dictated by the expectations/wishes

one has oneself. Now this is NOT the real personality, despite the fact that

people will assure that it is quite real and quite honest, yet it is not!

Such a “performance” or “role” of the persona is quite alright as long as you

know that you are not identical with the way in which you appear. But,

if you’re unconscious of this fact, then you get into, sometimes, disagreeable

conflicts: people can’t help noticing that at home you are quite different from

how you appear in public. People will deny that they are like that, but they

are! (…) Now, which is the real man? Is it the man at home or the man that

appears in public? This is a question of chicken and egg. Often, it is such a

big difference that you would almost be able to speak of a double-personality,

and the more pronounced it is, the more neurotic the man is. He thinks of

himself as “one” but everyone else sees him as “two”, and the two personalities

may sometimes clash!”

How has this concept

been butchered by pop-psychology? Everyone you go on Google and Youtube, you

will see too many articles that distinguish between the “fake self” of the

persona and the “true self” that hides between the persona. Yet this was not

Jung’s point, and it is not Jung’s psychology, but the psychology of single

moms on Facebook groups who think they are studying Jung. Jung simply

distinguished between multiple “false selves”, i.e., multiple personas, without

privileging any one of them as the “true one”. So if I act in one way in public

and in one way at home, it is not that one of them is the “true me” and one of

them is the “false me”, but that both of them are different versions of me that

are fake in their own way.

This is why the

persona is not a mask that hides and encapsulates your “true self”, it is a

mask that hides the other masks. Let’s say I have three personas: I act

differently based on whether I am at school, at work or at home. Then, the

“lie” of each persona is the fact that I am unlike the other two. Hence, my

school persona hides my work and home personas, my work persona hides my school

and home personas and my home persona hides my work and school personas, but

neither of the three hide my “true self”, since there is no such thing.

Thus, like in that unintentionally

profound Naruto episode, “behind the mask… there is another mask!”.

Jean Baudrillard made

a good point, in his book “Simulacra and simulation”, that “fakes” or “simulations”

are not always false/incorrect representations that mask a pre-existing

reality, but a fake that hides the fact that there no pre-existing reality in

the first place:

“Such

is simulation, insofar as it is opposed to representation. Representation stems

from the principle of the equivalence of the sign and of the real (even if this

equivalence is Utopian, it is a fundamental axiom). Simulation, on the

contrary, stems from the Utopia of the principle of equivalence, from the

radical negation of the sign as value, from the sign as the reversion and death

sentence of every reference. Whereas representation attempts to absorb

simulation by interpreting it as a false representation, simulation envelops

the whole edifice of representation itself as a simulacrum.

Such

would be the successive phases of the image:

-it

is the reflection of a profound reality;

-it

masks and denatures a profound reality;

-it

masks the absence of a profound reality;

-it

has no relation to any reality whatsoever;

-it

is its own pure simulacrum.

In

the first case, the image is a good appearance - representation is of the

sacramental order. In the second, it is an evil appearance - it is of the order

of maleficence. In the third, it plays at being an appearance - it is of the

order of sorcery. In the fourth, it is no longer of the order of appearances,

but of simulation. The transition from signs that dissimulate something to

signs that dissimulate that there is nothing marks a decisive turning point.

The first reflects a theology of truth and secrecy (to which the notion of

ideology still belongs). The second inaugurates the era of simulacra and of

simulation, in which there is no longer a God to recognize his own, no longer a

Last Judgment to separate the false from the true, the real from its artificial

resurrection, as everything is already dead and resurrected in advance.”

(Jean

Baudrillard, “Simulacra and Simulation”, Chapter I: The Precession of

Simulacra)

What if the ourselves are the simulacra, now? What if

the persona is precisely that image in the third stage, that does not hide my “true

self”, but instead hides the fact that there is none?

III. THE

EMBEDDEDNESS OF THE PERSONA IN SOCIAL CONTEXTS

Jung’s idea that we

behave differently in different contexts was a good start, but in my opinion,

he didn’t go far enough. I believe that in order to get an accurate portrayal

of the inner workings of intersubjectivity, Jung’s idea needs to be

“radicalized” and taken to the extreme. We need to take whatever he said about

the persona and multiply it by 10.

In order to do this,

let us think for a moment about what we mean a “context”. Jung says that

we act differently in different “situations” or “contexts” (ex: if you act

different at home than at work, then “home” and “work” would be the two

contexts). However, even though we usually intuitively understand what we mean

by context, Jungians (as far as I know) never attempted a rigorous definition.

What I want to point

out precisely is that “context” is NOT the same as “entourage”.

The social context includes, but is not limited to the entourage, that

is, the people who you are with. But what I call “the social context” in this

part of the book is a larger set that includes not only the people who are

seeing you, but also the time and space of interaction, as well as the sum

of all previous interactions in that time and space and with that group of

people. Thus, it would be hard for me as well to give a very rigorous

definition, since my conception of “context” is so all-encompassing and general

that it basically includes everything else other than the messages and the subject’s

persona in an environment. But one attempt at such a definition could be: the

social context is the union between:

1. the time of interaction,

2. the space of interaction,

3. the entourage of the interaction and

4. the sum of all previous interactions under any

subset of that entourage and/or any subset of the same space.

I hope that my

definition is as inclusive as possible, without dwelling into the realm of

vague meaninglessness. Why do I say “subset”? Because the context of the

interaction is dictated by the previous interactions not only under the same

identical formula (same people and same space), but by the previous

interactions under similar formulas. The more similar they are, the more it

contributes to the context, but any slight similarity will contribute at least

a tiny bit.

To give an example,

let’s say that the current “formula” of the interaction is this:

1. Entourage (the people interacting): Me, Bob and

Stacy

2. Space: At school

3. Time: Today

The context of the

interaction is the union between that entourage, that space and that time as

well as all the previous interactions that I’ve had with Bob without Stacy, all

the previous interactions that I’ve had with Stacy but without Bob, all the

previous interactions I had with either of them but not at school, as well as

all the interactions that I’ve had at school but without either of them two.

Now, the previous interactions that will have a more “similar” formula will

have a more profound effect upon the context: the previous interactions I’ve

had with both of them at school will have a more profound impact on the social

context than the ones that I’ve had with only one of them, or the ones that

I’ve had with both of them but outside school, etc.

Thus, Jung’s persona

can be re-understood through this slightly more rigorous definition of

“context”: if you behave differently under different contexts, then your

behavior can change only by changing one of those four variables: the entourage,

the space, the time or the previous interactions.

Going back to my

previous point, how do we “radicalize Jung”, as I said? This definition of

“context” radicalizes most points about Jung’s persona with the introduction of

the space and the time of the interaction. Under Jung’s psychology, it is

unclear whether “contexts” or “scenarios” (ex: “at home”, “at work”, “in

public”, “in private”, etc.) are limited to the entourage or not. For many

people, “different contexts” means “the people who are seeing me at that given

moment”. My ‘radicalizing’ point is that it is not only that, it is also

the time and the space of the interaction, and not to mention the previous

interactions as well!

What do I mean by

“space”? One century ago, the meaning of “space” would be quite literal, since

people interacted solely face-to-face, so it would refer only to the physical

space surrounding them. But since the invention of telephones (and after that,

the internet), communication can be long-distance as well. Now “space” includes

virtual spaces as well: various online “places” you can go in to

interact with people on the internet, for instance. Various spaces include

various websites, forums or apps: Reddit, Discord, Facebook, Instagram,

Tik-Tok, Tinder, WhatsApp and so on, but also the physical building you are in

if you are communicating face-to-face, or if you are outside, then the precise

location in your city, all the way to the details like the weather and the

crowdedness.

I insist on the space

as being, in certain particular-cases, the only variable that needs to

be changed in order to change your persona. This means that you can be with the

exact same group of people and yet interact differently based on the space you

are in, everything else equal. If you take this into account, it

completely amplifies Jung’s concept of the persona, since it is shaped not only

by the gaze of the people who are observing you, but also by the “dead

gaze” of the non-living objects that are “watching you” as well!

EXAMPLE 1: One example of this I already gave previously in the book1: Bumble dating vs. Bumble BFF. At the time of writing this book, you can download the Bumble “dating app” on your phone and alternate between using both sections of the app: a dating section that is “meant for” for finding relationships and a BFF section that is “meant for” finding friends. I put “meant for” in quotes, since no one forces you to use those sections for any particular purpose, thus dissolving into an invisible super-ego compulsion to enjoy, like an invisible moral-conscience or voice inside the back of your head pushing you in either direction, despite you “technically” not being forced to do anything. Again I will repeat the hypothetical scenario of two people using both sections of the app, and in one scenario they could only match on the dating section, and in the other scenario they could only match on the BFF section. Let’s say, for the sake of argument, that they have the same pictures and bio in both sections of the app, and they both know that they are both using both sections. Then, we are dealing with “technically” the same scenario: the same two people who are both looking for friendships and relationships at the same time under the same app with the same name, same pictures and same bio. Yet, somehow, it is likely in many cases for the two scenarios to turn out differently, since in the “dating section” of the app, you feel a different “invisible crowd of cameraman watching you” than in the “BFF section”; almost as if the app itself is judging you, despite the fact that the app is a non-living object. This is why we have to update Jung’s definition of the persona to include not only the behavior that is shaped by the gaze of living individuals, but behavior that is shaped by the gaze of non-living objects as well. I will give a bunch more examples.

EXAMPLE 2: This is a personal example. I have a friend

who I regularly talk to on both WhatsApp and on Reddit. We usually use Reddit

for longer messages, since it is an “e-mail type” messaging website, not a

“real-time” one like WhatsApp, but this is not a very rigid rule. A weird

behavior of us is that on WhatsApp, we talk in Romanian, but on Reddit, we talk

in English. It is the exact same person who I am talking to, about the exact

same topics, and under the exact same privacy (it is not like there is someone

that is monitoring our Reddit conversations but that is not monitoring our

WhatsApp conversations, or vice-versa). Yet, the app that we are using to

converse has an unconscious effect on your behavior. It took me years to

realize that I am doing this unconsciously, as an automatism. Even now after I

noticed I do it, I still continue to do it consciously, because after all this

time it feels “weird” to switch the language. Yet, for some absurd reason, it

does not feel weird to switch the language from one app to another multiple

times per week, but it feels weird to switch the language inside one app. Thus,

the app that we are using (WhatsApp/Reddit) is part of the “space” of the

context. The entourage of the context did not change (I am still talking to the

same person), but my persona did change! Thus, Jung’s idea that the

persona is only a compromise between how we want to seem to others and how

others want to see us is too limited, since the persona should also include the

gaze of the “non-living others” – the objects of the space. In other words, it

is almost like “Reddit” and “WhatsApp” are a third person in the

interaction, and we want to impress the app itself as well in a certain way. If

we talk in Romanian, “Mr. WhatsApp” gets angry, and if we talk in English, “Mr.

Reddit” gets angry, despite WhatsApp and Reddit not being any actual people.

EXAMPLE 3: Some people’s personas change depending on the

weather. If the weather is poor, they may get gloomier and more lethargic, and

if it’s sunny, they may get more energic, despite everything else being equal

(the people they are interacting with, etc.).

EXAMPLE 4: This is an example that most people who are

reading this have already lived a few years prior to me writing this book. In

early 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic started spreading like wildfire throughout

the globe, causing most countries to impose some severe restrictions upon our

social contexts. One thing that happened is that school and work went online.

Thus, just like in the Reddit/WhatsApp example with me and my friend, people

started behaving differently without realizing and without making any conscious

decision to do so. People simply intuitively grasped the “unwritten

rules” of each social context, and reacted accordingly. In my case, I was in

high school during that time, and before that, we were forced to wear school

uniforms when we came in physically at school. When we got online and started

doing classes on ZOOM, we were forced to have our webcams open, but not to wear

uniforms. This may seem like an obvious thing, your first thought/reaction

might now be “Why the hell would you wear uniforms if you’re doing online

classes?”, but think about it – from the mainstream Jungian understanding of

the persona, this does not make much sense. The entourage of the interaction

did not change, I was interacting with the exact same teachers and classmates as

before. And our webcams were open, so they could still see us. Yet, no one

expected us to wear uniforms and no one did so and no one complained about it,

everyone just “intuitively understood” that it is not the case anymore. Then it

hits you: at school, we do not wear uniforms because the teachers want to see

us in uniforms, nor because we want to be seen by the teachers in uniforms (as

Jung’s limited definition of the persona would lead us to believe – a

compromise between how we want to be seen vs. how others want to see us).

Instead, we were a school uniform because of the building we were in. It

is almost as if it was not the teacher’s gaze who we were conforming to, but

the school’s gaze! “The school” is not even a real person, yet it seems like it

was the school itself who we were forced to “perform for” by the school-uniform

rule. And it is the exact same scenario with online, remote work: many

workplaces forced you to keep your cameras on even while working remotely, and

yet people still dressed differently. This makes you realize that we do not

dress only for the people who see us (the exact same people still saw the upper

half of your body just as well!), instead you dressed for the building, almost

as if you wanted to impress the building itself. “The building” is part of what

I call “space” of interaction, and the space is part of the social context.

EXAMPLE 5: The color of the room you are in can

unconsciously affect your mood, and subsequently, your behavior and your

personality. You have slightly different personas depending on the color of the

walls of the building you are in, despite you interacting with the same people.

Take an unhealthy marriage between two spouses with anger issues, who live in a

house with red walls, and move them in a house with blue walls, and their

marriage may take an entirely different turn. Their personalities might change

and they might not even realize it.

EXAMPLE 6: Swimsuits and underwear look almost identical.

Yet, we are only comfortable being seen so revealingly when we are on a beach.

When we are in other contexts, like in a bedroom, we are not comfortable being

seen in a revealing swimsuit. This is not only due to the crowd: some people

may say that we feel comfortable being half-naked on a beach because there are

many people there, but put just as many people in a big building and a lot of

them will cover up. It is the beach itself that is the “cause-of-persona”, so

to speak. You could even make a social experiment where you take a photo of a

woman in bikini and put a green-screen behind her. Then you virtually edit the

picture to change the background: once you put a beach background, the second

time you put a bedroom background. Then you make two fake social media accounts

where you post each of the pictures. People’s reactions will be differently,

despite the girl and the swimsuit/underwear being the exact same, only the

background being changed. What is most interesting in this example is that the

relationship between the cause-of-behavior and the drawing-of-attention is

inversely proportional: the more of an impact it has on your behavior, the

less you pay attention to it. Thus, the thing you are paying attention to

the most (the woman) is the one that has the smallest influence on your

reaction to it, and the thing that you are paying attention to the least (the

background) is the one that has the biggest influence on your reaction.

These are enough

examples. What all of them resemble is Zizek’s popular “joke” about coffee: “The

hero visits a coffee shop and orders coffee without cream. The waiter replies:

sorry, we’ve run out of cream. Can I bring you, instead, a cup of coffee

without milk?”. This joke shows that what an object is not is part

of the identity of that object. “Coffee without milk” vs. “coffee without

cream” are the same only in the physical reality, but the surrounding context

can create an expectations, and the expectation of something to be there

when it is not is the definition of lack. Thus, lack (of either cream or

milk) can only exist through expectations, those expectations themselves

creating the discord between expectations vs. reality that we colloquially call

“lack”. But expectations themselves are part of “context”. Thus, “coffee

without cream” and “coffee without milk” are actually different, despite them

being “technically the same”, we will react differently to each. We can apply

the same logic to the persona: what if we are the coffee? What if

instead of a coffee, we have a human? Then, “coffee without cream vs.

without milk” is the same as: “me at work vs. me at home”, or “me

on Bumble dating vs. me on Bumble BFF” or “me at school in-person vs. me

in online classes” or “me on Reddit vs. me on WhatsApp” or “me

half-naked at the beach vs. me half-naked in a building” and so on. All of

these examples are examples of two things/people being “technically the same,

but different due to context”.

IV. RETHINKING

IMAGINARY PROJECTION

Both Lacan and Jung

were on the same page regarding certain aspects of the formation of the

illusionary nature of romantic attraction, even if they weren’t aware that they

agreed.

Carl Jung often talked

about anima and animus projection: where a man thinks he falls in love with a

woman, but in fact falls in love with his “anima” – his imaginary idea of what

a woman should be like, and vice-versa for heterosexual women and animus

projection. For Jung, love contained an imaginary aspect to it: an

element of inside yourself (an ideal, an internal representation of how the

other person is like or should be like, etc.) is falsely thought to exist “outside”

of yourself, in another person (hence the projection inside anima/animus

projection).

In the case of Lacan,

he made a similar point. He often said that “love is giving something that

you don’t have to a person that doesn’t exist” as well as “love is

giving something you don’t have to a person that doesn’t want it”. His work

is full of statements about how “there is no such thing as a sexual

relationship” and about the narcissistic nature of attraction. His main point

was essentially the same as Jung’s: you think you are attracted to someone, but

in fact you are attracted not to who they actually are, but who you think they

are, an image inside your mind of who they are. And when you find out the

difference in reality, your fantasy is shattered and you are left disappointed.

This image of who they

are is, in a way, a persona, but not your own persona, instead a

projected persona. Let’s call it “the other persona”. (Normally, I could borrow

terminology from Lacan or from some other author, but Lacan has been quite

vague and inconsistent in his use of terms like “small other”, “ideal-ego”, “objet

petit a” that, at this point, it would be better to just define a term of my

own to make sure that we are clear about its meaning.) The other persona(s) are

not the same as the others’ personas! Let us make a distinction between them:

1. The other personas are the images in my mind of

other people

2. The others’ personas are the images in their

minds of themselves

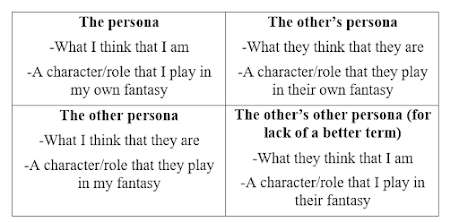

This is why “what I think of myself”, “what I think of themselves”, “what they think about themselves” and “what they think about me” are all four distinct categories. We called the first one “the persona” (what I think that I am), so let’s call the second one “the other persona” (what I think that they are) and the third one “the other’s persona” (what they think that they are). The other’s persona is an image of themselves in their mind, so I have no direct access to it (the fundamental alienation2 and so on…), hence it is not relevant to our analysis right now. Let us focus, instead, on the other persona(s).

The other personas are

the images in my mind of the other people. This is what goes on in Jung’s anima

and animus projection, instead of falling in love with someone else’s idea of

themselves, I fall in love with my idea of them. Why do I call it the other

persona? Because it is, in essence, a persona, a character, the other

person is playing a role. However, in this case, they are playing a role

in my story without realizing. That’s why when I am engaging in the (regular)

persona, I am usually at least somewhat aware that I am playing a character and

what it consists of (although even then, people can be unconscious of their own

personas, like Jung often warned!). In other words, the persona is the

character I play in my story. The other persona reverses this relationship

because it makes other people play a character in my own story, just like “what

they think that I am”, that is, “the other persona in their mind of me”, so to

speak, involves me playing a character in their story without realizing.

We can summarize these four relationships in a table:

The two categories on

the right side of the table are the two categories in their mind

(in the other person’s mind) and therefore are fundamentally inaccessible to

me. I can never think about them directly, we can never know what other people

think exactly. The two categories on the left side of the table are the

two categories from my own fantasy: the character I am playing and the character

they are playing. However, even though we can only consciously think of at most

two of these four categories (and sometimes even less, if we’re not aware of our

own personas!), it is important to remember that all four of these are usually

distinct categories. What I think that I am is different from what they think

that I am, and what they think that they are is different from what I think

that they are. This often creates a complex interplay of fantasies and

illusionary identifications, but it is precisely this illusionary element that

constitutes every human relationship.

But didn’t we already

know all this? What do I add to this, since so far it seems like old news?

Well, let us remember the previous chapter: all personas are embedded in a

social context. This is why feelings of attraction and repulsion: towards

your enemies, towards your lovers, towards your friends or towards your family

members, all of feelings towards a character that they play in your

fantasy, that character always having a backstory/context. Since any

persona (be it the regular persona or the other persona, in other words, any

theatric character) only exists inside a “story”, then you are not, say,

attracted only to the character, you are attracted to the entire story

behind them.

This has large

implications, since, let’s say, in the case of love (although not limited to

it: we do find the best and most “hardcore” examples wherever we find the most

passion, so the best examples of this concept are found in passionate love,

followed by rappers dissing each other), it means that you do not only fall in

love with your image of who they are, but with the entire story of who

they are: what is your relation with them, how they met you, how they are supposed

to act, how they should act from now on, where all of this is supposed to happen,

and so on.

That’s why it’s best

to think of the persona in terms of fictional characters inside a

theatre play or fiction novel, since there is no such thing as a fictional

character outside a fictional story. And if you fall in love with a fictional

character (your idea of who someone is: the other persona, or the projected

anima/animus, or whatever you want to call it), you automatically fall in love

with the story as well.

For a hypothetical example,

let’s think of a couple, a teenage boy and a teenage girl, who just met. They

soon fall in love, and thus, each of them constructs in their own mind a fictional

story not only about the other person, but about their relationship as a

whole.

Inside the girl’s

mind: the girl is a princess, and the boy is a knight in shining armor coming

to save her from the negative influences of the outside world and to protect

her from now on. In her mind, she is a fragile soul who must be protected and

treated gently, but with respect, and the boy she fell in love with is a

gentleman and a Don Quijote, courting women in chivalrous fashion. The girl

doesn’t only fall in love with the image in her mind of the boy, she falls in

love with the entire fictional story: they will get married, have lots of

children, he will protect her, he will fight with other man for her (be it

competitors, or fathers who want to destroy their relationship, or perhaps

teachers and other authority figures getting in their way at high school, or

whatever).

Inside the boy’s mind:

the girl is a slut, and himself is a bad boy and a manwhore looking for a

short-term adventure and they are both looking to party and have fun and take

risks. Again, the boy is not only in love with the imaginary version of the

girl in his mind (“a bad bitch”, “a sexy whore”, etc.), but with the entire fictional

story he constructed in his head: the risks they take, the excitement of the

possibility of getting caught doing something wrong by authority figures, and

so on.

Both of their phantasmatic

illusions can carry on due to the simultaneous imaginary-investment in similar “real

objects” in both of their lives. For example, the boy may already own a car or

a motorcycle, but for the boy, this represents a symbol of being independent

and rebellious towards authority (“I am a bad boy, I own a motorcycle!”), while

for the girl, this is a symbol for maturity and responsibility (“He is

independent and responsible, he already owns a vehicle, he will take care of

me, so he's a good boy!”). Hence, the boy’s personal motorbike is itself a different character in

each of the two stories!

Or, perhaps, the fact that parents and other authority figures in their lives are trying to separate them. For the boy, the parents are playing the role of the “cause-of-rebellion”: both him and his girlfriend are trying to have fun and some adventure while these boring adults are getting in our way, scolding us about how we are missing class too much! For the girl, the parents are playing the role of the “evil aggressors”, and she takes a much more serious attitude towards them. For her, the fact that they keep their relationship is more than a sign of “fun” rebellion and more of a story about a knight in shining armor saving her from the monsters and evil-doers keeping her “trapped in her castle”. Again, the secondary characters in their story are different characters in each of the two stories. We can redraw the table applied to this particular example:

This is again, to

show, how Jung’s original description of the persona was insufficient, since

for him, it was merely a compromise between how other people want to see us and

how we want to be. But since we already determined that the persona is always

embedded in a social context, it is not only about fictional characters,

it is altogether about fictional stories.

Through this new view

of the persona(s), we can take another look at the famous “Oedipal” love triangles

described by many psychoanalysts: how in any relationship between two people,

there is always an imaginary/invisible third presence getting in the way, and

so on. What if that imaginary third presence getting in the way is the other’s

persona? Thus, we can represent the “fall” or “break” of your phantasmatic

illusion as this: “If it weren’t for the other’s persona, I could be with

the other persona right now!” (in other words, if it weren’t for who you

think you are, I could be with who I thought you were!). This puts an entirely

different spin onto my favorite game described by Eric Berne in his book “Games

people play”: “If it weren’t for you” – we love to lie to ourselves

about how “if it weren’t for this obstacle getting in the way, I would have

surely gotten what I wanted” (think of the ending of every Scooby Doo episode

as an archetypal representation of this). But what if the ultimate formula of

this game was: “I could be with you, if it weren’t for you getting in the

way!”, that is “I could be with (my version of) you, if it weren’t for

(your version of) you getting in the way!”.

There is a graphical representation of this. The scheme of such imaginary projections is represented by (mathematically speaking) taking a complete graph with four nodes and then removing only one of the edges:

To this scheme, we

must add the labels of each persona from our previous example:

I’ve colored the boy’s

imaginary love triangle in blue and the girl’s imaginary love triangle in pink.

The boy’s failed fantasy is this: “The bad boy (who I think that I am) could

have been with the bad girl (who I thought that she is), if it weren’t for the princess

(who she thinks that she is) getting in the way!”. The girl’s failed

fantasy is this: “The princess (who I think that I am) could have been with

the knight in shining armor (who I think that he is), if it weren’t for the bad

boy (who he thinks that he is) getting in the way!”.

Notice how all four

personas in this graph are connected (that is, they have some sort of

interaction) other than the two on the bottom: the other persona and the other’s

other persona. In other words, we can phrase this like this: who I think

that you are and who you think that I am have never met and will never meet!

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

ENDNOTES:

1: Here is what I mentioned "previously in the book" about Bumble, such that you can have some more context:

"The simplest example of “coffee without milk vs. coffee without cream” that I can give in contemporary society is based on dating apps. The dating app “Bumble” has, at one point, introduced a “Bumble BFF” option next to its original “Bumble dating” mode, in which a person can match with other people to form friendships. Originally there were some restrictions on either mode, making them have different functionality, such as how in heterosexual relationships in the dating mode, only women were allowed to send the first message, and in the BFF mode, you could only match with people of the same sex, but they slowly removed all those restrictions. Now, it’s even possible to use the same profile with the same pictures in either mode. Why do I bring this up? Let’s consider the following hypothetical scenario:

I am single, and I use Bumble looking for both romantic relationships and friendships, and thus use both the Bumble dating option and the Bumble BFF option. Now this scenario branches into two alternate scenarios: in possibility 1, I match on Bumble dating with another person who is also using both Bumble dating and Bumble BFF at the same time, looking for both relationships and friendships, but I don’t match with anyone on the BFF option. In possibility 2, let’s say I match with the exact same person on the BFF option, but not in the dating option. Let’s also assume, for the sake of argument, that both of us know about each other’s use of both platforms of the same app.

These two scenarios are like coffee without cream vs. coffee without milk. In reality, they are the exact same scenario: two single, heterosexual people, who are looking for both relationships and friendships, match on an app to talk and get to know each other. However, in spite of the fact that the two scenarios have the exact same “input data” in reality, there is a chance that they might turn out differently in the end. In possibility 1, when the two people matched on the dating portion of the mobile app, it is as if they now have a crowd of invisible cameraman all watching them, like in those “Bachelor” shows, telling them “Come on! Mate! Reproduce! We are all waiting for you! Go enjoy each other!”. This “invisible pressure coming out of nowhere” is similar to what Lacan called the ego-ideal, or the “compulsion to enjoy”. In possibility 2, when the two people matched on the friendship portion of the mobile app, now it’s as if they have a crowd of invisible cameraman watching them and telling them to do the opposite, “Do NOT fall in love, stay friends!”. This latter crowd is more similar to the punishing/moralizing Freudian super-ego.

Even though in the two scenarios we are dealing with the exact same situation, the expectations are different – in the former situation, the two people are “supposed to” date, in the latter situation, the two people are “supposed to” be friends. However, the more important question lingers here: they are “supposed to” … by whom? Who exactly is it that is doing this pressuring, this “supposing”? There is no one reinforcing or punishing them for any choice they make. No one is watching their private conversations. And neither the guy, nor the girl are holding these expectations specifically. It is as if there is a third invisible element intruding in the conversation, a person that does not even exist, but is out there, subtly influencing us and manipulating the outcome of our relationship. It is exactly that presence that Lacan calls “the big Other”. The big Other, in a paradoxical way, does not even exist, but still has a profound impact on our reality. The big Other here can be „the dating app” or „that pop-up on the GUI that tells me in which mode of the app I am in” or even „nothingness itself”. It is the abyss of the void itself that has the biggest influence on the outcome of our social interactions. Under such circumstances, one can be tempted to ask questions such as „Who are you giving your power to when you are using these apps?” and „When you match on such an app, are you even dating the person you match with, or are you dating the dating app itself?”. This is why, if I were the CEO of Bumble, I would resolve such situations by matching the two people on the app „in general”, without specifying whether they matched on the dating version of the app or the friendship version of the app, the app would simply tell you that you are both looking for both friendships and relationships, without pressuring you in either direction – this would likely simulate real-life a bit more."

2: The "fundamental alienation" is my term for the fact that your red is not the same as my red, essentially.

Cool post, but in a Jungian framework there is definitely a “true self” that you are sidestepping/not considering here — so it is more of a repurposing and blending of a Jungian concept rather than a radicalizing imo.

ReplyDelete