What is socially constructed? | Class vs. Identity, The Big Other and Second-Order Cybernetics

The “social construct” is

a common buzz-word nowadays. We often times hear that various identity groups

or concepts are socially constructed, sometimes with the implied notion that

this makes them less important for our attention. But to simply separate all of

our experience in a strictly binary way between “real” and “socially

constructed” is an extreme oversimplification. For example, money is a social

construct, but fiat money (with flexible exchange rates, post-1971) is, for

lack of a better word, “more” of a social construct than money that is tied

to a gold standard. In other words, there are layers to this.

The aim of this essay is

not to provide a complete system, theory or guide on how to separate what is

real from what is socially constructed in a way that could explain everything.

Rather, we will look at various specific themes of interest for our analysis

and how they relate to the topic of social construction: Marxism and ideology,

Lacanian psychoanalysis, the relationship between class and identity politics

as well as the tools that cybernetics and systems theory can offer us. In the

first part of this essay I will focus on Lacan’s theory of the big Other and

how it connects with Marx’s and Zizek’s theories of ideology. In the second

part, I will connect this to Niklas Luhmann’s sociological theory of

second-order cybernetics. In the third part, I will use that gathered knowledge

to analyze the implications for class and identity politics.

I:

THE BIG OTHER AND IDEOLOGY

Psychoanalyst

Jacques Lacan differentiated early on in his work the way in which every social

interaction and act of communication is structured by a double-relation towards

the agent whom we are communicating with. On one hand, I am addressing myself

towards a “small other”, on the other hand, I am simultaneously addressing

myself towards a “big Other”, with a capital O. While the meaning of the small

other changed throughout his work, for the purposes of this essay we are defining

it as our internal image of the other person1 – the specific

individual human being we are talking to. The big Other, on the other hand, is

the locus of the a priori conditions for communication to take place – hence it

includes all the unwritten rules and implicit assumptions of any social

interaction. The big Other acts as a presupposed “as if” – even if there may

be, say, only two people in a room talking, they act “as if” there was a

third invisible presence hearing them.

The big Other is present

in our everyday “honest lies” and in every act of indirect communication, of

hints, euphemisms and ‘redundant censorship’: I am lying to you, you know that

I am lying, I know that you know that I am lying and yet we continue to

play-pretend (“as if” we were spied on by an invisible presence, even when we

aren’t). Here is an example of the big Other in action from Zizek’s

introduction to Lacan2: in a group when we all think of a dirty

detail and we all know that everyone knows it, we nonetheless may feel embarrassed

when someone blurts it out, despite no one learning any new information. Why?

Because we lose the freedom to pretend that we don’t know (in Lacanian

language: the big Other now knows).

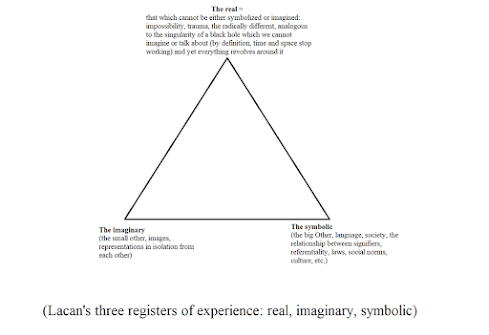

Whereas

the small other is situated in the imaginary order, the register of

experience containing inner representations of ‘things’ in isolation from each

other (images), the big Other is situated in the symbolic order, the

register of experience containing referentiality and connections. The symbolic

order is the register occupying language and meaning, since all communication

is founded on references (like a pointer in programming or a vector in linear

algebra – constantly displacing you from one location to another).

Since the symbolic order of language and

communication is founded not upon ‘things’ but between the relationships

between them (as creators of meaning), it can be used as a framework for analyzing

relationships not only between words but also between people through words.

Since a signifier (ex: a word), according to structuralist theory, only has

meaning in relationship to all the other signifiers (through contrast), it is the

difference between various particulars inside a whole that has priority

over their individual identities to create the meaning of that whole. We might

say, with a little exaggeration, that the whole is not the sum of its parts,

but the “difference of its parts”. Michel Foucault gave in an interview a

wonderful analogy for structuralism3: imagine you have a photo of

someone on your computer and you apply a negative filter on top of it. All the

white pixels turn black, all the black pixels turn white, all pixels of some

other color change as well. No pixel is of the same color at an individual

level, and yet you can still recognize whose face is in the picture – why? Because

while all individual pixels changed their color, they all changed in the same

way. Despite “nothing being the same” in the picture, the overall image is

nonetheless still easily recognizable, because the relationships between the

pixels have remained the same. In Lacanian terms, we can say that while the

imaginary register has changed completely (all particular “things” have changed

if we analyze them in isolation), the symbolic order has stayed the same. If,

in this analogy, we replace pixel with ‘word’ (or more generally, with ‘signifier’)

and the overall photo with “language”, then this is how structuralism conceives

of communication. If, instead, we replace the pixel with “human” and the

overall image with “society”, then we can conceive of a structuralist theory of

society. The conclusion is properly anti-humanist: society is not made up of

individual human beings, but of relationships between individuals.

Why

does this matter? Zizek gives another example that perfectly illustrates this theory

in action4: let’s imagine we have a family celebrating Christmas and

they all pretend to believe in Santa Claus when they are together. But let’s

say that now someone takes them individually, when the other people can’t hear them,

and asks them in private whether they really believe in Santa Claus. The

parents will reply “Of course we don’t believe, but our children believe in

Santa so we also pretend to believe so that we don’t disappoint them and ruin Christmas”.

But then if you take the children and ask them privately, they might say “Of

course not, we’re not idiots, but we pretend to believe so that we don’t

disappoint our parents and we get presents”. The conclusion is counter-intuitive

at first: no one believes at an individual level, yet they all believe as a

group. It’s enough for everyone to presuppose that someone else might

believe, without that presupposition being true, for the belief to function in

a group of people. For Zizek, this is how ideology functions in society as well,

in our political and social lives. This is why it is not important whether a

dangerous ideology is adopted by a ‘vocal minority’ on social media – the force

of an ideology is not the number of individual human beings who agree with it,

it might as well be believed by no one in particular and it can still take

effect (recall the infamous: “I was just following orders” in Nazi Germany,

where one can make a compelling argument that the number of individual humans

during the holocaust who genuinely believed in the fascist cause was not as

high relative to the atrocities it caused).

For

Karl Marx, in his famous analysis of commodity fetishism, the market of goods

is not a relationship between commodities, but a relationship between people mediated

by commodities. “Capital is not a thing, any more than money is a thing. In

capital, as in money, certain specific social relations of production between

people appear as relations of things to people, or else certain social

relations appear as the natural properties of things in society.”5.

Can’t we ascribe a similar process of ‘reification’ to ideology? Ideology is

not a mere relationship between ideas or beliefs. It is a relationship between

people that appears to us as ideas. Belief systems are not just a set of relationships

between ideas in each individual human being’s brain, they are a “real fiction”

– a very real and material relationship between people that appears to us as a

relationship between beliefs. This puts an important twist to our ordinary

usage of the term “social construct” – our ideological superstructure is

socially constructed only insofar as it is the manifestation of a real and

concrete set of social relationships (in the same way that the gestalt that was

“the picture of someone’s face” in the pre-mentioned analogy was a “non-real manifestation”

of a set of relationships between real and concrete pixels on a screen). In our

critique of ideology, we must thus not look for the hidden meaning ‘behind’ the

form, the so-called essences beneath the appearances, like in Plato’s allegory

of the cave. The real mystery is how the essence hides inside the appearance itself,

the content not behind the form, but within the form itself. Thus the task

is not to find what hides behind the illusory appearances of our ideology, to

take the “mask off” and see reality for what it is, without its social

constructs; but instead to ask ourselves what happened in the movement

from reality to appearance, why did that content take this particular form out

of all forms?6

II:

LUHMANN’S SECOND-ORDER CYBERNETICS

Sociologist

Niklas Luhmann used cybernetics and systems-theory to provide a similar theory

of “radical constructivism”. Despite Zizek never mentioning him (to my

knowledge) in any of his books, their theories have many convergences.

For Luhmann,

society is not made up of humans but of social systems. Various social systems,

like the economy, law, politics, art, etc. are each autopoietic and operationally

closed. This means that each system produces changes inside its own system

and cannot directly interact with other systems. Instead, the entirety of

society can be viewed through the perspective of one system. Politics and law

can be analyzed economically, the economy, art and love can be viewed through

the perspective of the laws surrounding them, etc. By operational closure, we

mean that the system produces its own division between itself and its

environment. Thus, the classical “subject/object” division inside philosophy is

replaced with the “system/environment” distinction7. Two

systems that are structurally coupled can each irritate each

other to provoke changes inside themselves. A system can only directly change

itself (by definition); hence structural coupling is when a change inside one

system can irritate another system to also change itself. Political parties can only directly make

changes in the system of politics, not directly influencing the economy. For

instance, a tax increase is a change by the law system of the law

system, and it only irritates the system of the economy to

also make changes inside itself. Social activism in academia cannot directly

change the system of politics to take measure against, say, climate change -

the most it can do is make changes inside itself and hope that the system of

politics will also change itself accordingly.

Crucial

to Luhmann’s social systems theory is his definition of an observation: “An

operation that uses distinctions in order to designate something we will call

'observation'. An observation leads to knowledge only insofar as it leads to

re-usable results in the system. One can also say: Observation is cognition

insofar as it uses and produces redundancies - whereby 'redundancy' here means

limitations of observation that are internal to the system.”8. In

other words, an observation is a distinction (between that which is observed

and everything else) executed by a system that produces knowledge for the

system itself. In order for my visual-psychic system to observe a cat in front

of me, I must distinguish it from everything else that is ‘not-cat’: the

background, the trees next to it, the asphalt on which it is walking, etc. This

information is only valuable when fed back into the same psychic system that

did the distinction in the first place. The system of the economy can observe

an economic transaction by distinguishing it from everything which it is not, but

this already presupposes that we view all reality in economic terms of prices

and transactions. My biological system can observe something as part of itself

only by distinguishing it from intruders like viruses, which can in turn

activate a reaction from the immune system (and through the perspective of my biological

systems, all of physical reality is viewed in biological terms). The system of

science can observe something as true by distinguishing it from falsity, but this

presupposes that all of reality is viewed through the true/false distinction,

etc.

This

of course leads to the problem of infinite recurrence that lies at the heart of

all transcendental philosophy: if any observation already presupposes that we

view reality from a certain perspective, then who we are to say that the ‘blind

spot’ from which we view reality is indeed the adequate one? Can’t we have a

meta-system of observing the systems from which we observe reality? But who

will decide that one, so we can get a meta-meta-system and so on to infinity

(recall the infamous ‘if God created the universe, then who created God?’

question which similarly leads to the same infinite loop that was first faced

head-on by Kant). For Luhmann, finding an unbiased or “absolute” standpoint

that is unmediated by a higher point of observation is not important. The

observation of an observation is simply called “second-order observation”

– it is a “meta” observation, so to speak. As Hans-Georg Moeller explains: “A

first-order observation can simply observe something and, on the basis of this,

establish that thing’s factuality: I see that this book is black—thus the book

is black. Second-order observation observes how the eye of an observer

constructs the color of this book as black. Thus, the simple ‘is’ of the

expression ‘the book is black’ becomes more complex—it is not black in itself

but as seen by the eyes of its observer.”9.

While

the implications for transcendental philosophy of this theory are numerous and

outside the purposes of this essay, we can look towards the sociological

implications. As society is not made up of humans, but of social systems, and

each social system can also observe itself observing reality (through second-order

observation), this “meta” standpoint provides further possibilities for the

social construction of reality. Economist John-Menyard Keynes unintentionally

described second-order observation by trying to explain how the stock market

functions through the following comparison:

“Professional

investment may be likened to those newspaper competitions in which the

competitors have to pick out the six prettiest faces from a hundred

photographs, the prize being awarded to the competitor whose choice most nearly

corresponds to the average preferences of the competitors as a whole; so that

each competitor has to pick, not those faces which he himself finds prettiest,

but those which he thinks likeliest to catch the fancy of the other

competitors, all of whom are looking at the problem from the same point of

view. It is not a case of choosing those which, to the best of one’s judgment,

are really the prettiest, nor even those which average opinion genuinely thinks

the prettiest. We have reached the third degree where we devote our intelligences

to anticipating what average opinion expects the average opinion to be.”10

In

other words, in order to gamble on the stock market, it is not enough to try to

predict the future value of a stock, the very attempt at this prediction

implies predicting how other people will predict as well. Thus, the first-order

observation of the future market-value of a stock turns into the second-order observation

of other investors’ first-order observations of its future value. Therefore, the

question of investment quickly jumps from “what do other people think?” to “what

do other people think about what other people think?”. Or, one can take a

similar example taken from Moeller’s book on profilicity in the age of social

media11: if I present myself the way I would like to be seen on

social media, this is an example of first-order observation in action. I post a

selfie, a girl looks at it and thinks “he’s so hot!” – she observes me as good

looking. But if I present myself the way I would like to be seen as being

seen, I move to second-order observation: a girl looks at my selfie and how

many likes it already has and thinks “Damn, other girls probably think he’s

hot” and likes the selfie as well. In the latter case, no one needs to

believe that I look good, everyone just needs to assume that other people

believe that I look good and it functions just as well. If this sounds similar

to Zizek’s Santa Claus example of how belief works, it’s because it is. We can

sum up the connection between Luhmann’s social systems theory and Lacan’s and

Zizek’s theories of reality as this: first-order observation

works on the level of the imaginary order and the small other, while second-order

observation works on the level of the symbolic order and the big

Other. At the level of the “animal” imaginary register of experience, I distinguish

between various particular (images) in isolation from each other, drawing

boundaries that define objects. In the “human” symbolic order, I distinguish between

various relationships between particulars (ex: relationships between words in a

language), that is, I distinguish between distinctions, which is the

definition of Luhmann’s second-order observation. If Lacan was correct in his

theory that what separates humans from animals is the capacity to acquire

language, and consequently, the access to the symbolic order (society, culture,

social norms), then one implication of this statement is that only humans have

the capacity for second-order observation while animals are stuck in the imaginary

order of first-order observations.

To

conclude this theoretical mess of jargons: the Lacanian big Other is the

environment of a system under conditions of second-order observation: “Accordingly,

the market is the environment of economic organizations and interactions

internal to the economic system, and public opinion is the environment of

political organizations and interactions internal to the political system”12.

An abstract notion like “the market” does not reflect the behavior of one

particular consumer or producer participating in it, but the aggregate of

expectations about what each participant in the market “thinks about what other

people think about” something. A similarly vaguely-defined notion as “the public

opinion” is the political system’s big Other: not the opinion of one particular

voter, but the accumulation of what each voter thinks about what other voters

think, and so on.

With

this in mind, it should come as no surprise that the big Other appears as most

evident in those social situations in which something changes despite no new information

being learned by any particular individual in it. Niklas Luhmann, borrowing

from Gregory Bateson, defines information as “any difference which makes a

difference in some later event”13. However, the very way in

which we can distinguish between what is and isn’t a difference already

presupposes the particular standpoint of one specific system: a difference in

what, exactly? Information for my visual system means a difference in my visual

perception that makes a difference for my visual perception. Scientific

information is a difference inside academia which makes a difference inside

that very same academia. Under conditions of second-order observation however,

a system observes its own observations and what counts as ‘information’ is not

a change in whatever was initially observed under the conditions of first-order

observation, but a difference in first-order observations that makes a difference

in first-order observations. Let’s now re-examine our early example of that awkward

social situation in which everyone is thinking of a dirty joke, everyone knows

that everyone knows, and yet we all avoid saying it out loud. In Lacanian

terms, we would say that we don’t want the big Other to know that dirty detail,

so we continue to pretend that no one knows. The paradox here lies in how, if

we were to say out loud what everyone is thinking, no one would learn any new information

and yet the mood would be ruined. With our new definition of information (as a difference

which makes a difference), we can understand why: new ‘information’ was

nonetheless registered at the level of second-order observation. Every

individual in the room observed how other people’s observations changed and ‘the

mood’ (that is, the “big Other’s mood”, not the emotional state of any

particular human individual) was thus ruined.

Without

the human capacity for second-order observation (that is, the Lacanian symbolic

order), no social system can exist, and thus no society and no state. To give a

similar example that involves the social system of the law: Where I live in

Romania, we also had a Youtuber that was doing a similar version of that “To

Catch a Predator” show: he would make fake accounts online where he

pretended to be a minor below the age of consent, pedophiles would message his

account and flirt with his fake account, they would plan to meet up in person

and he would show up and call the police on them. However, now in Romania we do

not have a strong law against child grooming, and thus, it’s only illegal to

make explicit sexual demands for a minor below the age of

consent. The groomers would flirt with his fake account thinking it was a

real underage girl while always having the legal precedent that they “technically”

did not break the law. This gave rise to the similar social situation in which

the police were called, and everyone (the groomer, the Youtuber, and each

individual cop) knew what the pedophile’s real intentions actually were, and yet

nonetheless they had to go through the entire legal hurdle anyway. If each

individual human being in the courtroom knows what the accused individual is

guilty of grooming, who are they exactly communicating with when they are

trying to find “legal evidence” for such an action? They are interacting with a

set of laws created by humans for humans, and yet nonetheless this set of laws “catches

a life of its own”, so to speak (in a similar way to Marx’s commodity

fetishism) – they are talking “as if” there is an invisible presence in the

room that has zero social skills and does not understand the pedophile’s real

intentions, and it's that non-existent presence (i.e.: the big Other) that we must

prove ourselves to.

The

social system of science has similar functions. When a mathematician ‘proves’ a

theorem that everyone already knows it’s true, they are not convincing any

particular human being that the theorem is true, but instead the big Other of

the mathematical system. In Luhmannian terms, the above examples are instances

of the system of law and the system of science working under conditions of second-order

observation. No one believes at an individual level that the pedophile was

innocent or that the theorems are false, but everyone behaves as if they

presupposed that someone else might believe. The belief is displaced onto the

Lacanian “subject supposed to (not) know”.

III:

CLASS VS. IDENTITY POLITICS AS SOCIAL CONSTRUCTION

With

our current analysis we can now re-examine our conception of the social

construction of reality. When people are making a claim that various group

identities (such as those studied by frameworks like intersectionality: race,

gender, ethnicity, etc.) are socially constructed, we can view this either

through the perspective of first-order or second-order observation.

For

Niklas Luhmann, the claim that all of reality is socially constructed would be

meaningless without further context – yes, but constructed by what? In order

for us to have any access to an “objective reality”, one must already observe it

from the particular standpoint of one specific system. Since each cybernetic

system produces its own reality, we can say in our jargon that all my psychic

reality is psychically constructed by my brain, all the reality of social

systems like law and the economy are socially constructed, etc. This is not a

claim that tangible, concrete reality “does not exist” at all. Like Luhmann

explains: “Operational constructivism has no doubt that an environment exists.

If it did, of course, the concept of the system's boundary, which presupposes

that there is another side, would make no sense either. The theory of

operational constructivism does not lead to a 'loss of world', it does not deny

that reality exists. However, it assumes that the world is not an object but is

rather a horizon, in the phenomenological sense. It is, in other words,

inaccessible. And that is why there is no possibility other than to construct

reality and perhaps to observe observers as they construct reality.”14.

Therefore,

to say that a group identity is socially constructed would require us to further

approach this question from a particular perspective of a system. Identities

are socially constructed by the system of law in and for the system of

law when they are registered by the specific legislature of that nation. An

individual’s psychic system constructs identities by drawing imaginary borders

around particular groups and treating them differently (either consciously or unconsciously).

When such distinctions are drawn in each person’s psychic system en masse

and incentivized through the mechanisms of other systems like law or the

economy (perhaps, a manifestation of the popular yet overused terms like “systemic”

racism/sexism/etc.) then we can say that those identities are both psychically

and socially constructed in a complex interplay and exchange of information between

each of the systems.

There

is, however, a problem in putting economic class on the same ‘level of

comparison’ like other identity groups such as race and gender, since they do

not operate on the same level of observation. Identity primarily functions at

the level of first-order observation. To experience homophobia, for example, I

do not technically need to actually be gay/bi, as long as a group of homophobes

believe that I am gay for some reason I can still experience it. As long as I “pass”

as a certain race to a racist, it does not matter whether I literally am

that race or not (rather, the question does not even make sense – to “be”

something according to what system?) – I will experience racism. We are still

on the level of first-order observation here: as long as the discriminating

agent acts upon their distinctions, I will be treated differently in society

regardless of what I think. Recall here the infamous joke repeated in Lacanian

circles about the schizophrenic patient: "a man who believes himself to

be a grain of seed is taken to a mental institution where the doctors do their

best to convince him that he is not a seed but a man. When he is cured

(convinced that he is not a grain of seed but a man) and is allowed to leave

the hospital, he immediately comes back trembling. There is a chicken outside

the door and he is afraid that it will eat him. 'My dear fellow,' says his

doctor, 'you know very well that you are not a grain of seed but a man.' 'Of

course I know that,' replies the patient, 'but does the chicken know it?'”15.

Economic

class functions at the level of second-order observation. Your economic class

is not given by what the small others (individual humans) think you are but by what

the big Other believes you to be. Class is, thus, socially constructed, but at

another level and in a different way than identity. Class is a relationship

between people that cannot temporarily disappear when the psychic system of the

“small other” (person) in front of you changes their beliefs. You do not need other

people to believe you are ‘poor’, for instance, and to have them change their

behavior towards you based on that judgment, in order for you to experience the

consequences of your exploitation. In fact, it is entirely possible to hide your

economic status from all your peers, to lie to everyone that you are rich, and

it is inevitable: it will be impossible to make any purchase on the market as

long as you do not have the money. In order for you to become “rich”, it is not

enough to convince many individual human beings around you that you are - you

have to convince the big Other of the economic system (the “market”) to change

the numbers in your bank account. By fighting economic exploitation, we are not

merely fighting “classism”: a set of prejudices and stereotypes about poor and/or

working class people that causes them marginalization in society (in the same

way one would fight bigotry), instead we are referring to the more ingrained

and fixed “real belief” of the big Other of the economic system itself – a relationship

that structures capitalism as such. Capitalism does not create or “cause” economic

exploitation in the same way that it can make use of ideological

superstructures like bigotry and religion to perpetuate itself: instead it is

the economic exploitation that is the foundation of capitalism. The bourgeoise

and the proletariat are not two different classes that first exist, and then

they come into conflict. Without one, the other’s existence is impossible: a bourgeoise

can only exist with a proletariat to exploit it and vice-versa, and thus it is again

the conflict or difference which comes first - initially we have the

class conflict not between two particular classes but the conflict-in-itself,

and the two poles (classes) gravitating around it like planets around the sun.

We thus come at a

properly dialectical paradox: Marxist theory compares the seemingly “concrete

and material” relations of production (the base of society) that give rise to economic

exploitation to the ideological superstructure of society gathered by people’s

beliefs, attitudes, prejudices, stereotypes, culture, etc. Under the premise of

Orthodox Marxist historical materialism, one may conclude that in order to

change people’s ideas one must first change their concrete material conditions.

An (oversimplified, for the sake of argument) example of this is how a

materialist might say that “poverty causes racism” while an idealist might say

that “racism causes poverty”. If we follow the logic of historical materialism

to the very end, to simply raise awareness about social prejudices and change

people’s mentalities is useless as long as we do not change their concrete

material conditions – solving poverty and homelessness would do much more to

help racism and sexism rather than the other way around. The paradox lies here

in noticing how what is considered “concrete and material” in the economic

bases of society lies under double levels of abstraction: it is the conditions of

second-order observation, a belief about beliefs, that constructs the “hard

and material” objective reality of money. The Hegelian “negation of negation”

here shows its work again: our production of the material, concrete things one

can touch (like factory machinery) already are created through a

double-negation of this very reality itself – an abstraction of abstraction.

NOTES:

1: I say “internal image” because our inner representation

of another person may not match their inner representation of themselves. The

Lacanian small other is similar if not identical to the concept of “internal

object” in object-relations theory (for a short introduction, see: “N. Gregory

Hamilton – Self and Others: Object Relations Theory in Practice).

2: Slavoj Zizek, “How to read Lacan”, p. 25

3: Michel Foucault – The Lost Interview: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qzoOhhh4aJg

4: Slavoj Zizek, “How to read Lacan”, p. 29

5: Karl Marx, Capital Volume 1: A Critique of Political

Economy, p. 1005

6: See: Slavoj Zizek – The Sublime Object of Ideology,

Chapter 1: “How did Marx invent the symptom?”

7: Niklas Luhmann, “The Cognitive Program of

Constructivism and a Reality That Remains Unknown”: “The mistake here lies

in the assumption that it is possible to describe an object completely (we

won't go so far as to say 'explain') without making any reference to its

relation to its environment (whether this relation be one of indifference, of

selective relevance and capacity for stimulation, of disconnection, or of

closure). In order to avoid these problems, which arise from the point of departure

taken, both subjectivist and objectivist theories of knowledge have to be

replaced by the system-environment distinction, which then makes the

distinction subject-object irrelevant.”

8: Niklas Luhmann, ibid.

9: Hans-Georg Moeller, Luhmann Explained: From Souls

to Systems, p. 72

10: John-Menyard Keynes, The General Theory of

Employment, Interest and Money, p. 100

11: See: Hans-Georg Moeller, “You and Your Profile:

Identity After Authenticity”

12: Niklas Luhmann, The Reality of The Mass Media, p.

104

13: Niklas Luhmann, ibid., p. 18

14: Niklas Luhmann, ibid. p. 6

15: Slavoj Zizek, How to Read Lacan, p. 93

Nice essay, I appreciate your use of Luhmann

ReplyDeleteExcellent read as usual. I found your blog while lurking r/stupidpol and now I check back regularly anticipating your next banger.

ReplyDeleteGreat stuff! Have you thought of moving to Substack?

ReplyDelete